Hanuman Langur/ Gray Langur

Semnopithecus entellus

North & Central India

Langur, a general name given to numerous species of Asian monkeys belonging to the subfamily Colobinae. The term is often restricted to nearly two dozen species of leaf monkeys but is also applied to various other members of the subfamily. The Colobinae or leaf-eating monkeys are a subfamily of the Old World monkey family that includes 61 species in 11 genera, including the black-and-white colobus, the large-nosed proboscis monkey, and the gray langurs.

Semnopithecus is a genus of Old World monkeys native to the Indian subcontinent, with all species with the exception of two being commonly known as Gray Langurs. Traditionally only the species Semnopithecus entellus was recognised, but since about 2001 additional species have been recognised. The taxonomy has been in flux, but currently eight species are recognised.

Members of the genus Semnopithecus are terrestrial, inhabiting forest, open lightly wooded habitats, and urban areas on the Indian subcontinent. Most species are found at low to moderate altitudes, but the Nepal Gray Langur and Kashmir Gray Langur occur up to 4,000 m (13,000 ft) in the Himalayas. The langur we know as the Hanuman Langur is the Northern Plains Gray Langur.

Understanding Hanuman Langurs and their role in the jungle is crucial to finding the alpha predators like tigers. The tiger is a truly majestic creature. It is the alpha animal in the jungle and for good reason. Moving with a fluid grace that no other animal can match, padding silently, a tiger can creep up on any creature and kill them with a single swipe of the outsized paws. Once those thorn shaped claws rip at you, it is all but over. The tiger is phantom silent and melts into the bush like molten gold into a cast. When the tiger finds a good ambush site, it lurks in the shadows, waiting for prey to pass, observing everything with glittering, feline eyes. When the target appears, it pounces with a coiled energy that is both fearsome and pitiless.

When one is in the vast, dense jungles of India, and the tiger one hopes to document could be anywhere in that jungle, the only sense that can be relied on is hearing. Finding paw prints and signs of activity will show what happened on the night’s hunt, but once the animal vanishes into the tangled undergrowth the only way to track it is to stand and listen for a call. Not from the tiger itself, but an alarm call from potential prey alerting their fellow animals to the location of the predator. This is a phenomenon one has to experience, but first, what exactly is an alarm call?

Alarm calls are calls given by animals lower in the food chain, potential prey animals, when they detect the movement of an apex predator. Monkeys, deer and even birds give alarm calls. It is a very short, high pitched and high intensity call. When an apex predator, a tiger or a leopard, is spotted these alarm calls warn the herd that the predator is on the prowl. So when we hear these, we listen for the intensity, how far the call has come from and how reliable it is. What do I mean by reliable? One of the first and most useful vocal indicators are the Bandar Log - Hanuman Langurs, perched in the high branches able to see the predator from afar, who amazingly use a barking alarm call for leopards and a different call for tigers. Their call indicates that a predator is on the move and by finding the direction of their gaze the general direction of the predator can be gauged. Experienced guides can also determine, based on the intensity and tone of the call, whether the predator is a tiger or a leopard. Chital, favourite prey of tigers, quickly respond to the langurs call and begin a persistent barking of their own. And finally one of the most defined calls to listen for when tracking is given by sambar deer, who make a guttural squeak and stamp their feet when they spot the tiger. And when the tiger is out on the hunt this is an explosion of alarm calls from different animals that echoes through the jungle.

Northern Plains Gray Langur near the the Pandharpauni Lake, Tadoba Andhari Tiger Reserve

Almost at the heart of the nation lies the jewel of Vidarbh, “Tadoba National Park and Tiger Reserve”. Also known as the "Tadoba Andhari Tiger Reserve" it is the oldest and largest National Park in the state of Maharashtra and one of 47 Project Tiger reserves existing in India.

Tadoba is a jungle where, early in the day, the sun follows one like a lodestar through the tangled heads of the trees and as the day progresses it burns with a blinding exquisiteness that makes us shield our eyes and bless our existence. The light is lustrous in the open spaces and seemed undistllled from heaven to earth seeming like a laser show at times as gem clear beams filter through the trees. The warmth of it settles over our faces like a silken mask and life is a golden joy. That is the thing about the seraph-light of this jungle; it can sweep down like the handloom of the gods one moment, pure and clear and long of line.

Tadoba lies in the Chandrapur district of Maharashtra state, once ruled by the Gond Kings in the vicinity of the Chimur Hills, and is approximately 150 km from the closest major city, Nagpur. The total area of the tiger reserve is 1,727 km², which includes the Tadoba National Park, created in the year 1955. The Andhari Wildlife Sanctuary was formed in the year 1986 and was amalgamated with the park in 1995 to establish the present Tadoba Andhari Tiger Reserve. The word 'Tadoba' is derived from the name of God "Tadoba" or "Taru," venerated by the local adivasi (tribal) people of this region and "Andhari" is derived from the name of the river Andhari flowing in this area. Legend holds that Taru was a village chief killed in a mythological encounter with a tiger. Taru was deified and a shrine now exists beneath a large tree on the banks of the Tadoba Lake. The temple is frequented by the adivasis between the months of December through January.

Home to some of central India’s best native woodland bird species, about 181 including endangered and water birds, the park also boasts leopards, sloth bear, the Indian bison (Gaur), Nilgai, Dhole, Striped Hyena, small Indian Civet, numerous Jungle Cats, Chital (Axis Deer), Sambhar, Barking Deer, Four-horned antelope, Marsh Crocodiles, a profusion of Langurs and Rhesus Macaques and a good measure of reptiles like the Indian Python, Cobra and numerous other species. Tadoba, unfortunately, also has a high rate of man tiger conflict. Several instances have also been reported of wildlife killing domestic livestock and there are villages still within the forest contrary to the efforts of the Forest department so we were told. Note it is man conflicting with nature and not the other way round.

As of May 2020, there were 115 royal bengal tigers, 151 leopards estimated in Tadoba and the surrounding buffer areas. A booming population supported by the incredible and diverse biodiversity making the reserve a paradise for tiger enthusiasts who have the choice of some of the best forest tracks in the country.

This is not a reserve where one will say I saw a bengal tiger, here one will say I saw the Telia Sisters, I saw the huge Matkasur, I saw beautiful Maya, I saw the gorgeous Choti Tara. Tadoba today has probably the highest Sighting Rating Index (SRI) for the tigers in the country with SRI defined as the number of successful sighting safaris vs the total number of safaris undertaken in the prior 28 days.

Read more about Tadoba and its wildlife.

Pench National Park, nestled in the heart of India in the lower southern reaches of the Satpura hills, sprawls a massive 758 km² across the states of Madhya Pradesh & Maharashtra. In Madhya Pradesh it is located in the districts of Seoni and Chhindwara. Named after the pristine River Pench it was immortalised by Rudyard Kipling in his Jungle Book. Every year millions make their way here to spot Akela (the Indian Wolf), Baloo (the Sloth Bear), Bagheera (the Black Panther) and Shere Khan (the Royal Bengal Tiger). It was declared a sanctuary in 1965 and elevated to the status of national park in 1975 and enlisted as a tiger reserve in 1992. The area has always been rich in wildlife dominated by fairly open canopy, mixed forests with considerable shrub cover and open grassy patches. The high habitat heterogeneity favours a high population of Chital and Sambhar. Pench tiger reserve has highest density of herbivores in India (90.3 animals per km²).

Pench has a glorious history of natural wealth and unique cultural richness described in several classics ranging from the Ain-e-Akbari to the Jungle Book. Several natural history books like Strendale’s “Seonee - Camplife in the Satpuras” & Forsyth’s “Highlands of Central India” present a detailed panorama of these forests.

The forest, lush and green in the monsoon, also harbours a wide range of faunal species some of which figure prominently in the IUCN Red List. Our story, however, is about the Hanuman Langur (Semnopithecus entellus) - also known as the Northern Plains gray langur, sacred langur and Bengal sacred langur. The Hanuman Langur is a species of primate in the family Cercopithecidae.

Pench National Park also was the location used by the BBC for the innovative wildlife series Tiger: Spy in the Jungle, a three-part documentary narrated by Sir David Attenborough which used concealed cameras, placed by elephants, in order to capture intimate tiger behaviour and also retrieved footage of various other fauna in the reserve. The programme aired for the first time in March 2008 and ended a month later.

Read more about Pench and its wildlife.

Semnopithecus

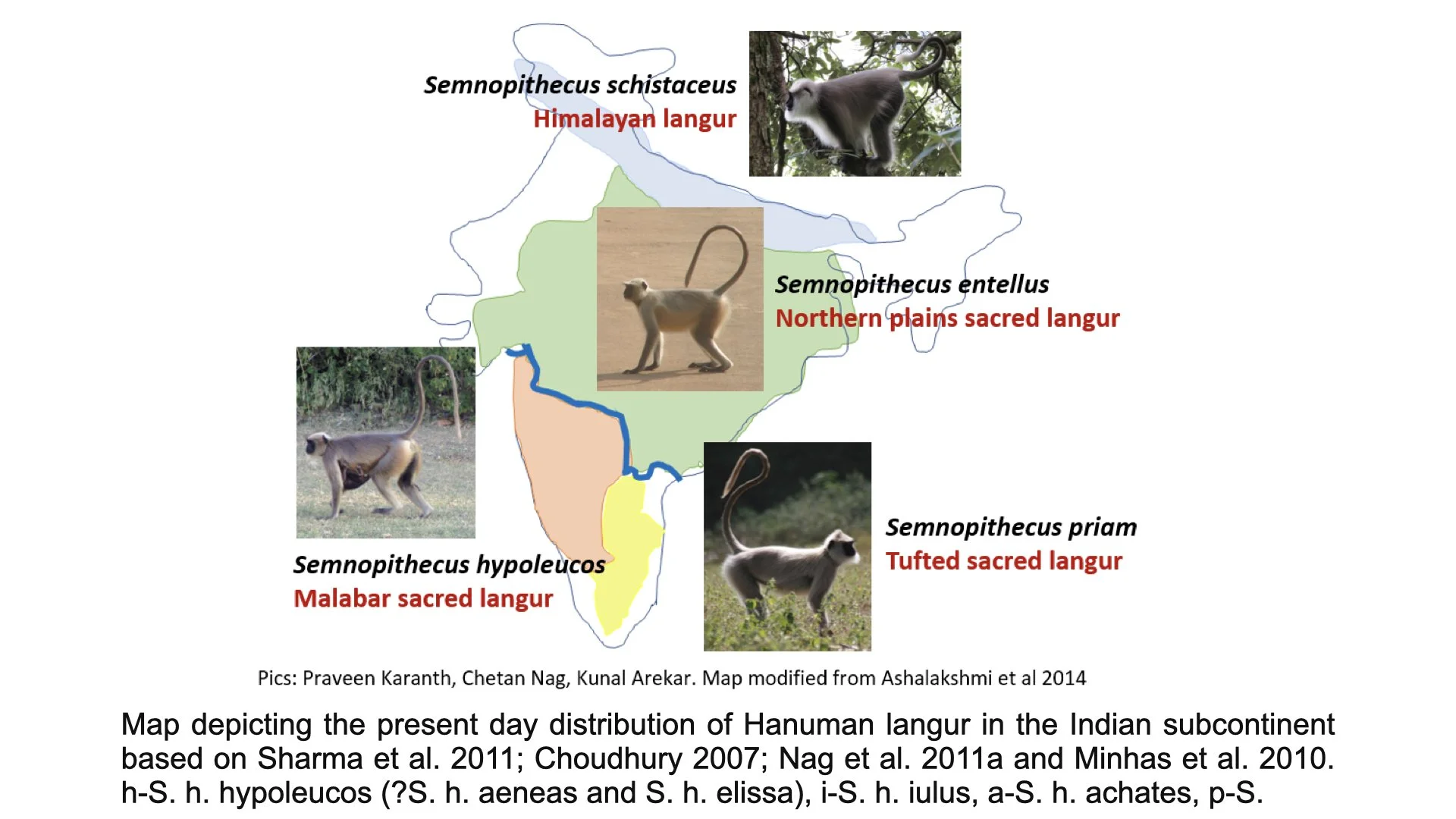

Semnopithecus is a genus of Old World monkeys native to the Indian subcontinent, with all species with the exception of two being commonly known as gray langurs. Traditionally only the species Semnopithecus entellus (Northern Plains Gray Langur) was recognised - the remainder all being treated as subspecies, but since about 2001 additional species have been recognised. The taxonomy has been in flux, but currently eight species are recognised.

Members of this genus Semnopithecus are terrestrial, inhabiting forest, open lightly wooded habitats, and urban areas on the Indian subcontinent. Most species are found at low to moderate altitudes, but the Nepal gray langur and Kashmir gray langur occur up to 4,000 m (13,000 ft) in the Himalayas.

As of 2005, the authors of Mammal Species of the World recognised the following seven Semnopithecus species

Nepal Gray Langur Semnopithecus schistaceus

Kashmir Gray Langur Semnopithecus ajax

Tarai Gray Langur Semnopithecus hector

Northern plains Gray Langur Semnopithecus entellus

Black-footed Gray Langur Semnopithecus hypoleucos

Southern plains Gray Langur Semnopithecus dussumieri

Tufted Gray Langur Semnopithecus priam

Results of analysis of mitochondrial cytochrome b gene and two nuclear DNA - encoded genes of several colobine species revealed that Nilgiri and purple-faced langurs cluster with gray langur, while Trachypithecus species form a distinct clade. Since then, two other species have been moved from Trachypithecus to Semnopithecus:

Purple-faced langur Semnopithecus vetulus

Nilgiri langur Semnopithecus johnii

In addition, Semnopithecus dussumieri has been determined to be invalid. Most of the range that had been considered S. dussumieri is now considered S. entellus.

Thus the current generally accepted species within the genus Semnopithecus are:

Black-footed Gray Langur (Semnopithecus hypoleucos) (Blyth, 1841) - Considered to have three subspecies (S. h. achates, S. h. hypoleucos, S. h. iulus) - Distributed across a small band from Goa to Kerala along the coastline. Their body is about 41–78 cm long with a 69–108 cm long tail and their habitat is forest and shrubland and their diet consists of leaves, fruit, and flowers. Status: Least Concern

Kashmir Gray Langur (Semnopithecus ajax) (Pocock, 1928) - Found in a tiny pocket in the Himalayas in the Kashmir region. Their body is about 41–78 cm long, with a 69–108 cm long tail. They favour forest habitats and live on leaves, bark and seeds. Status: Endangered

Nepal Gray Langur (Semnopithecus schistaceus) (Hodgson, 1840) - These are found in a long belt of the Himalayas all the way from Afghanistan, across J&K, Ladakh, Nepal, Bhutan and Sikkim. Their bodies are 41–78 cm long with a tail 69–108 cm long. They favour forest habitats, shrublands and rocky areas. Their diet consists of leaves, fruits, seeds, roots, flowers, bark, twigs, coniferous cones, moss, lichens, ferns, shoots, rhizomes, grass, and invertebrate animals. Status: Least Concern

Nilgiri Langur (Semnopithecus johnii) (J. Fischer, 1829) - Found in tiny patches in the Nilgiris these langur are about 41–78 cm long in their bodies with a 69–108 cm tail. They frequent forests and subsist on leaves, fruit and flowers. Status: Vulnerable

Northern Plains Gray Langur (Semnopithecus entellus) (Dufresne, 1797) - This is the species we see most commonly across North and Central India. They are about 41-78cm long with a 69-108cm long tail. Their favoured habitats are forests, savanna, and shrubland and they thrive on a diet of leaves, fruit, flowers as well as insects, bark, gum and soil. Status: Least Concern

Tarai Gray Langur (Semnopithecus hector) (Pocock, 1928) - Found in a small belt from Himachal Pradesh into Nepal in the Himalayas, North Bengal and Bhutan. They have a 41–78 cm long body with a 69–108 cm long tail. Their favoured habitat is forests and their diet consists of leaves, fruit and flowers. Status: Near Threatened

Tufted Gray Langur (Semnopithecus priam) (Blyth, 1844) - Like the Black-footed this too has three subspecies (S. p. anchises, S.p. priam, S.p thersites). They are distributed on the east end of the Deccan from Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, some parts of Tamil Nadu and Sri Lanka. They have a body 41–78 cm long with a tail 69–108 cm long. They prefer forest and shrubland habitats and their diet consists of leaves and fruit. Status: Near Threatened

Purple-faced langur (Semnopithecus vetulus) (Erxleben, 1777) - This has four subspecies [T. v. monticola (Montane purple-faced langur), T. v. nestor (Western purple-faced langur), T. v. philbricki (Dryzone purple-faced langur), T. v. vetulus (Southern lowland wet zone purple-faced langur)] and is found only in Sri Lanka. Its body is about 41–78 cm long with a 69–108 cm long tail. They prefer a forest habitat and survive on leaves, fruits, flowers and seeds. Status: Endangered

A 2013 genetic study indicated that while S. entellus, S. hypoleucos, S. priam and S. johnii are all valid taxa, there has been hybridisation between S. priam and S. johnii. It also indicated that there has been some hybridisation between S. entellus and S. hypoleucos where their ranges overlap, and a small amount of hybridization between S. hypoleucos and S. priam. It also suggested that S. priam and S. johnii diverged from each other fairly recently.

Hanuman Langur/ Northern Plains Gray Langur

The Northern Plains Gray Langur (Semnopithecus entellus), also known as the Sacred Langur, Bengal Sacred Langur and Hanuman langur, is a species of primate in the family Cercopithecidae belonging to the genus Semnopithecus along with the other Indian langurs. The Southern Plains Gray Langur was once classified as a subspecies of S. entellus, i.e., S. entellus dussumieri and later regarded as a separate species, i.e., S. dussumieri, but is now regarded as an invalid taxon. Most of the specimens that had been regarded as Semnopithecus dussumieri fall within the revised range of Semnopithecus entellus.

The fur of the adults is mostly light colored, with darker fur on the back and limbs, and the face, ears, hands and feet are all black. Infants are brown. The body size excluding the tail ranges from 45.1 cm (17.8 in) to 78.4 cm (30.9 in) long, and the tail length is between 80.3 cm (31.6 in) and 111.8 cm (44.0 in). Adult males weigh between 16.9 kg and 19.5 kg while adult females weigh between 9.5 kg and 16.1 kg.

The range of the northern plains gray langur covers a large portion of India south of the Himalayas south to the Tapti River and the Krishna River. It is thought to have been introduced to western Bangladesh by Hindu pilgrims on the bank of the Jalangi River.

The Hanuman langur is diurnal, and is both terrestrial and arboreal. Its natural habitats are subtropical or tropical dry forests and subtropical or tropical dry shrubland. Females groom members of both sexes but males do not groom others.

The Hanuman langur can live in several different types of groups. It can live in groups of multiple males and females, one male and multiple females or multiple males with no females, and males can also live alone without a group. Single male groups are most common and group sizes can exceed 100 monkeys. Upon reaching maturity, males typically emigrate from their natal group while females typically remain. Young adult females are typically dominant over older females. When a new male takes over a group it may engage in infanticide of young fathered by the previous male or males, but this is less common when the takeover occurs slowly over several months.

These langurs primarily feed on fruits and leaves and are able to survive on mature leaves, which is a key to its ability to survive throughout the dry season. It also eats seeds, flowers, buds, bark and insects, including caterpillars. It is also fed fruits and vegetables by humans, and some groups get a substantial portion of their diets from food provided by temples and from raiding crops.

Groups that have access to abundant food year-round, for example those that are provisioned by temples or are able to raid crops year-round, also breed throughout the year. Other groups, such as those living in forests, typically give birth between December and May. The gestation period is about 200 days. Females other than the mother alloparent (a term used to classify any form of parental care provided by an individual towards young that are not its own direct offspring) the infant for the first month of its life. Weaning occurs at about 1 year and males reach maturity at about 6 to 7 year old.

The Hanuman langur often associates with chital or Axis deer. Both species respond to each other's alarm calls. The chital seem to benefit from the vigilance of male langurs watching for predators in the trees, while the langurs seem to benefit from the chital's better senses of smell and hearing. It also has been observed engaging in grooming sessions with rhesus macaques. Listen to the build of calls starting with the langurs, then the chital and finally the Sambhar announcing the arrival of the tiger.

The Hanuman langur is listed as least concern on the IUCN Red List, but it is threatened by habitat loss. The Hanuman langur adapts to many habitats and the Hindu religion considers them to be sacred. Hence it has large population within India, including within towns and cities. It is subject to some threats, including road kill, attacks by dogs, forest fires and diseases caught from domestic animals. It is sometimes hunted for food, especially within the states of Odisha and Andhra Pradesh and is sometimes killed by humans to prevent it from raiding crops.

‡‡‡‡‡

Related Posts