Short-eared Owl

Asio flammeus

Bhigwan Bird Sanctuary & Yenkathala Grasslands, Telangana

Kumbhargaon, a nondescript village in the Satara district to the south of Bhigwan, a quaint, small and rugged town on the border of the Pune and Solapur districts in Maharashtra, in India. During its mild winters, Kumbhargaon, Bhigwan and its surrounding areas become the home of countless migratory birds making it the “Bharatpur of Maharashtra”. The area around Bhigwan and the River Bhima is vast and unique with diverse habitats ranging from the shallow wetland ecosystem of the Ujni backwaters to the surrounding rich farmlands and dry deciduous scrub forest with interspersed grasslands.

Surrounding this lush ecosystem are rich grasslands and fertile farms home to an impressive list of birds, mammals and reptiles. A few of the beautiful birds of prey I have already written about in the two earlier series -

The Eagles - the endangered Steppe, the vulnerable Greater Spotted, and rare & also vulnerable Eastern Imperial

The Harriers - the Pallid, the Montagu’s & the Eurasian Marsh

The open areas around the villages also host mammals like the black-naped hare, jungle cat, golden jackal, and Indian grey mongoose. The Asian palm civet can also be seen, especially at night. The extensive grasslands protect many mammals like the Chinkara, Hyena, Wolf and Indian fox. While largely unnoticed, frogs, toads, damselflies, dragonflies, beetles, and scorpions also inhabit the area. A study published by the Zoological Survey of India in 2002 reported 54 species of fish.

I will now talk about the other raptors seen in these magnificent grasslands starting with the stunning Short-eared Owl.

During our time here we were hosted by and had the expert help of Sandip Nagare and his team of knowledgeable guides from the Agnipankha Bird Watcher group, especially Ganesh Bhoi, who went out of their way to ensure we had fantastic opportunities to explore, discover, observe & photograph over 82 species of birds and wildlife including some rare ones. We stayed at Sandip’s homestay of the same name and had the added pleasure of indulging in delectable home cooked food.

Yenkathala/ Enkathala Grasslands

About 60 kilometers from the capital city of Hyderabad in Telangana lie the Yenkathala or Enkathala grasslands. Apart from the multitude of birds and winter migrants, the rare Indian Grey Wolf has also been spotted here along with a number of foxes. The dry deciduous forests ecoregion of the central Deccan Plateau covers much of the state, including Hyderabad. The characteristic vegetation is woodlands of Hardwickia binata and Albizia amara. Over 80% of the original forest cover has been cleared for agriculture, timber harvesting, or cattle grazing, but large blocks of forest can be found in the Nagarjuna Sagar - Srisailam Tiger Reserve and elsewhere. The more humid Eastern Highlands moist deciduous forests cover the Eastern Ghats in the eastern part of the state. The Central Deccan forests have an upper canopy at 15–25 meters, and an understory at 10–15 meters, with little undergrowth.

Grasslands are natural carbon sinks and therefore crucial to the global carbon cycle due to their high rates of productivity, enhanced carbon sequestration rates & geographical extent keeping global temperatures more or less in balance. They are also breeding grounds for many migratory and endangered species like the Indian Grey Wolf of which only about 3,000 are left in the wild. It is a common response from people to think forests when green cover is mentioned but grasslands are of equal import. These open natural ecosystems urgently need attention and government initiatives for protection and conservation. In Telangana, grasslands are located in the districts of Vikarabad, Nizamabad, Khammam, Siddipet and Nalgonda. The wildlife in these fragile ecosystems today face numerous threats like hunting, spread of the canine distemper virus which affects foxes, wolves & several other species, rabies from feral dogs and most crucially, habitat loss.

‡‡‡‡‡

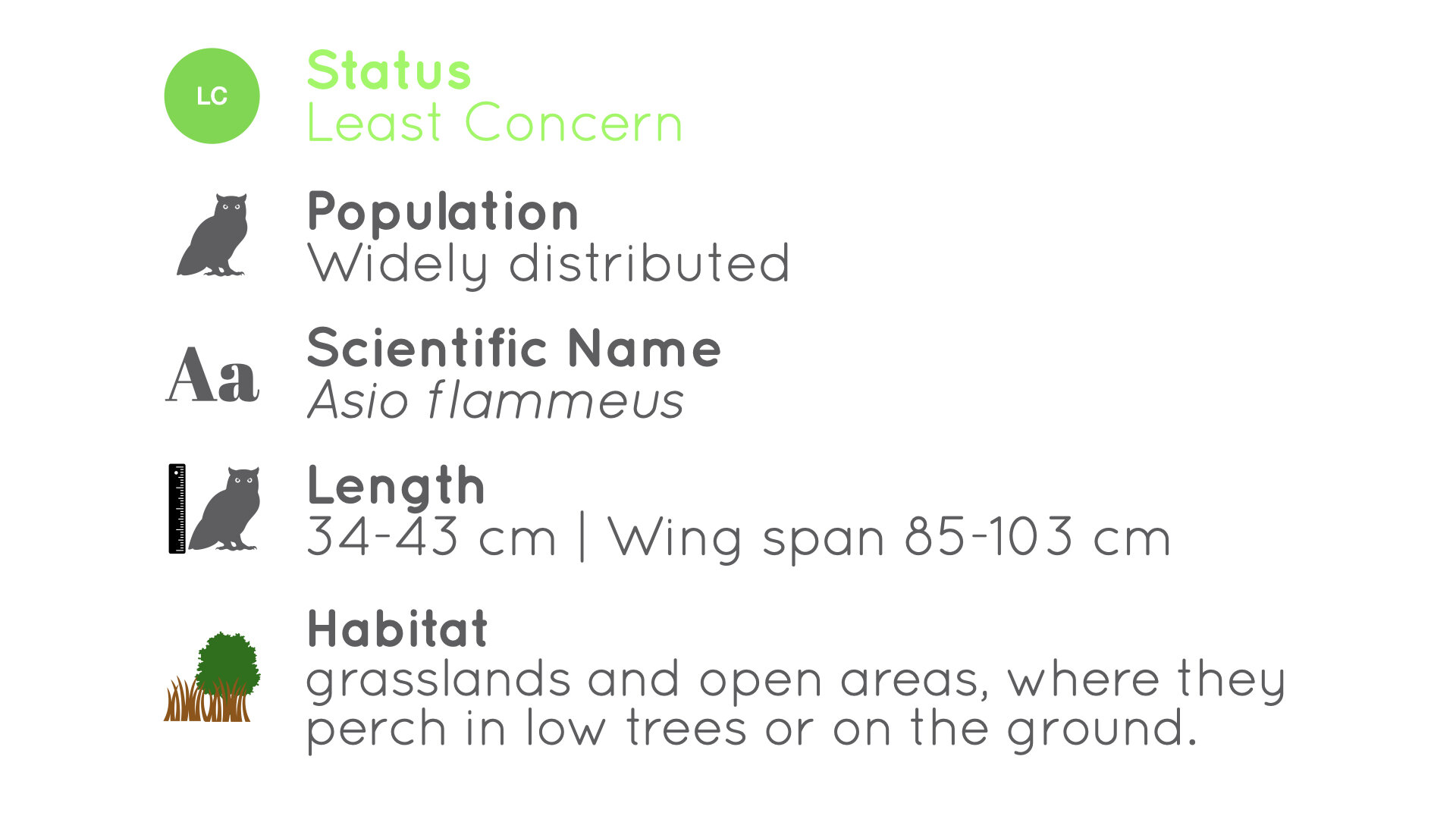

The Short-eared Owl

The Short-eared Owl (Asio flammeus) is a widespread grassland species in the (family Strigidae). Owls belonging to genus Asio are known as the eared owls, as they have tufts of feathers resembling mammalian ears. These "ear" tufts may or may not be visible. Asio flammeus will display its tufts when in a defensive pose, although its very short tufts are usually not visible. The short-eared owl is found in open country and grasslands.

This medium-sized owl is more frequently seen in the daytime than other owls. Especially active around dawn and dusk, when it flies lazily over open fields or marshes in search of small mammals. Overall rather pale brown, palest on belly, with streaks and spots on wings and chest. Large buffy patch near the wingtips easily visible in flight. The females are a darker brown than the males. Rarely heard vocalizing away from breeding grounds, where it makes a low series of hoots and a variety of harsh barking noises.

Through much of its range, short-eared owls occurs with the similar-looking long-eared owl. At rest, the ear-tufts of the long-eared owl serve to easily distinguish the two (although long-eared owls can sometimes hold their ear-tufts flat). The iris-colour differs: yellow in the short-eared, and orange in the long-eared, and the black surrounding the eyes is vertical on the long-eared, and horizontal on the short-eared. Overall the short-eared tends to be a paler, sandier bird than the long-eared.

Easier to see than most owls, the short-ear lives in open terrain, such as prairies and marshes. It is often active during daylight, especially in the evening. When hunting it flies low over the fields, with buoyant, floppy wingbeats, looking rather like a giant moth.

The short-eared owl occurs on all continents except Antarctica and Australia; thus it has one of the most widespread distributions of any bird. A. flammeus breeds in Europe, Asia, North and South America, the Caribbean, Hawaii and the Galápagos Islands. It is partially migratory, moving south in winter from the northern parts of its range. The short-eared owl is known to relocate to areas of higher rodent populations. It will also wander nomadically in search of better food supplies during years when vole populations are low.

Hunting occurs mostly at night, but this owl is known to be diurnal and crepuscular as well. Its daylight hunting seems to coincide with the high-activity periods of voles, its preferred prey. It tends to fly only feet above the ground in open fields and grasslands until swooping down upon its prey feet-first. Several owls may hunt over the same open area. Its food consists mainly of rodents, especially voles, but it will eat other small mammals such as mice, ground squirrels, shrews, rats, bats, muskrats and moles. It will also occasionally predate smaller birds, especially when near sea-coasts and adjacent wetlands at which time they attack shorebirds, terns and small gulls and seabirds with semi-regularity. Avian prey is more infrequently preyed on inland and centers on passerines such as larks, starlings, and pipits. Insects supplement the diet and short-eared owls may prey on cockroaches, grasshoppers, beetles and caterpillars.

Although it is widely distributed this too, like so many others, has a declining population. It has disappeared from many southern areas where it formerly nested. Loss of habitat is probably the main cause. It is listed as declining in the southern portion of its US range. It is common in the northern portion of its breeding range. It is listed as endangered in New Mexico. Climate change is also affecting populations. Audubon’s scientists have used 140 million bird observations and sophisticated climate models to project how climate change will affect this bird’s range in the future to see how this species’s current range will shift, expand, and contract under increased global temperatures. Some of the climate threats facing this beautiful owl are wildfires which incinerate habitat, and if they burn repeatedly, prevent it from recovering and the spring heat waves which endanger young birds in the nest.

Another factor specific to the Kumbhargaon grasslands is the uncontrolled chasing and flushing the bird out for the sake of some likes on social media. A number of people trekked through the grasslands trampling the habitat, killing/ scaring the prey of the owl and then there were at least 30 cars of different sizes recklessly driving all over the grasslands - both on and off track - trying to get close to the owl. As my video shows the owl was constantly alert and agitated watching all the cars rather than hunting and feeding and being its natural self.

When we first saw the owl, it was flushed out by a “guide“ some 50 feet from where we had been parked for a few hours. It then took off into the trees about 300 meters away and thus began the chase. About 30 cars rampaged through the grasslands and trees chasing the owl. We were trying to make our way to it on foot but each time there was a car which got too close to get a “frame filling Nat Geo shot“ and drove the owl further into the brush. This frustrating exercise continued for almost an hour which, from the birds perspective was harrowing, to say the least. The owl eventually went so far into the dense brush that it was no longer possible to pursue on 4 wheels thankfully, but some still persisted in pursuing on foot despite all efforts otherwise.

Some of the “guides” guaranteed that they will flush the owl back out again and ventured into the scrub in their vehicles. Eventually, after another 30 minutes or so, the owl came out and perched on an acacia tree as seen in the first part of my video. While it was perched on the acacia which was bordering the track, the first car was immediately outside the bottom left of my frame. Our driver, despite all resistance, decided to cut through the grassland from one track to another, and got stuck on an earthen rise with the car balanced down the middle and rocking back and forth creating the movement you see in the first half of my video. Getting the car off the mound involved a lot of drama and manpower which was accomplished after some genius drivers in close proximity to the owl started their cars and revved. Once off the mound and back on the track our driver insisted on pursuing the owl but I told him I was no longer interested in what I had just seen and experienced. The entire exercise went against everything I know and believe while photographing birds or any wildlife and will most certainly scare away the birds and destroy the habitat if not controlled. A similar thing happened with the harriers as well.

it is unfortunate to see such uncontrolled behaviour by so called wildlife lovers and enthusiasts. These areas are the threatened and fast disappearing Deccan thorn scrub forests and grasslands. Read more about these here and here for if the habitat disappears so do the birds and animals.

‡‡‡‡‡

The following are some photos of the Short-eared Owl recorded on the grasslands. We saw the owl in multiple phases starting with our tracking through the woods to where it was perched on the acacia tree and then much later when it came and perched on a stone in the grasslands. Thankfully while it was perched on the stone, the terrain surrounding it was rough and could not be driven over even by the 4WDs that were present. The time spent here was beautiful as the owl was about to start hunting and was looking around in all directions. It also gave us an opportunity to observe it interact with the other species of the grasslands like a drongo which kept harassing it.

Also note in the video the tufts are visible - Asio flammeus will display its tufts when in a defensive pose, although its very short tufts are usually not visible when it is relaxed.

A brief note on Owl behaviour

An Owl's daily activity begins with preening, stretching, yawning and combing its head with its claws. The plumage is often ruffled up, and claws and toes are cleaned by nibbling with the beak. The Owl will then leave its roost, sometimes giving a call (especially in breeding season). Owls have very expressive body language. Many species will bob and weave their head, as if curious about something - this is in fact to further improve their three-dimensional concept of what they are viewing.

When relaxed, the plumage is loose and fluffy. If an owl becomes alarmed, it will become slim, its feathers pulled in tightly to the body, and ear-tufts, if any, will stand straight up - as observed in our case. A pygmy Owl will cock its tail and flick it from side to side when excited or alarmed. Little owls bob their body up and down when alert.

When protecting young or defending itself, an Owl may assume a "threat" or defensive posture, with feathers ruffled to increase apparent size. The head may be lowered, and wings spread out and pointing down. Some species become quite aggressive when nesting, and have been known to attack humans.

Read about the other owls I have seen and photographed and a couple I have already detailed.

These were the first few images made while we were tracking the owl after it was flushed out from the grasses. Most of us, I think, were on foot trying to work our way closer before the cars started to show up and drove the owl further into the brush.

These next few photos were also taken from a fair bit away as the owl was agitated and kept a wary out on the intruders. In the first two photos I had some brush between me and the bird I was hoping would blur out and didn’t so I had to move a few feet to the front and right. In the third photo the owl had its eyes closed but in the fourth it is looking to where all the cars were and in the fifth towards where we were all trying to sneak up from. The two above and the ones below were all at 600mm so you can imagine how far the bird was.

This next sequence of photos is when the owl came and perched on the acacia and we were trying to make our way to it. This was well before the mass of cars arrived on the scene and we were about a 100 meters from it. After this our driver decided to cut across the grasslands - despite all discouragement from our end - to get ahead of the crowd and ended up getting stuck.

Now we got to about 25 meters from the bird - also we were well and truly stuck across the middle on an earthen mound with both the front and back wheels of the car suspended in air. By this time the entire crowd had arrived and there was no point in trying to get ahead because the nearest car was just a few meters away from the bird and any more movement would have driven the bird away. From here I tried different combinations with the 1.4x and 2x (840mm and 1200mm) extenders to get the photos.

After spending a good 45 mins on the tree the owl took off when the cars at the back started to squeeze in closer and went into deeper brush. We decided to leave it to its devices and came out looking for the fox. Unfortunately there was a crowd of people already waiting for the fox and it did not make sense to join the mob. So we drove over a couple of ridges to wait it out and hope that we would see something. About three quarters of an hour later our guide said that the owl had come out fairly close to where we were and was perched on a rock amidst the grassland. There weren’t too many cars and we slowly made our way there and these are some of the photos.

After giving us an amazing time to observe and photograph it the owl took off again away from us and perched beyond what I think was a nullah - a shallow watercourse clothed with rough brushwood or small trees growing in the stony soil. During occasional heavy rains, torrents rush down the nullahs and quickly disappear.

There I saw an interesting incident with a Black Drongo.

A bully, a mimic, an attacker: the Black Drongo

The habit of drongos in general of being pugnacious in defence of its nest and territory by attacking all predaceous enemies, is quite similar to that of crows. It is a common sight to see these birds chase after owls and eagles in the air, swooping at them with an agility in flight only attained by falcons. This chase is accompanied by a series of angry chattering calls that attract the attention of the least observant species — humans! Their aggressive behaviour often sees them land on larger birds of prey, like owls and eagles, and peck at them repeatedly to drive them away. The sequence below is one such split second instance between a black drongo and the short-eared owl.

The owl was perched at some distance from us near a depression in the grasslands. The light was fading and I was focused on the owl to catch any specific movements or behaviour. Out of the blue this black drongo came swooping down at quite a high speed and tried to peck the owl on its head. Equally swift was the owl’s reaction of ducking its head in an almost human like response.

Thankfully at 1200mm (EF 600mm f/4L IS III+Extender EF 2x III) the owl was far enough to accommodate the entire sequence and I was able to fire off a quick burst as soon as I spotted the drongo and realised what it would do. Note the raised tufts indicating the defensive posture of the owl.

To truly experience the moment and to see the split second reaction keep your eyes locked on the owl and let your peripheral vision handle the drongo. You will see and experience what I felt at that moment with one eye glued to the camera viewfinder and the other open.

This aggressive behaviour of the drongos towards birds of prey and general marauders encourages gentle species like doves, orioles, and bulbuls to nest in the vicinity. These birds find protection in the territories of drongos and thus prefer nesting in their relative safety.

These were our final moments spent with this beautiful owl as it perched on the rocks by the nullah. Watching and recording it was an absolute pleasure and an honour to be able to get close to this predator of the grasslands.

The following footage was recorded on 12th February on the grasslands near Shirsupal at the Bhigwan Bird Sanctuary.

Related Posts