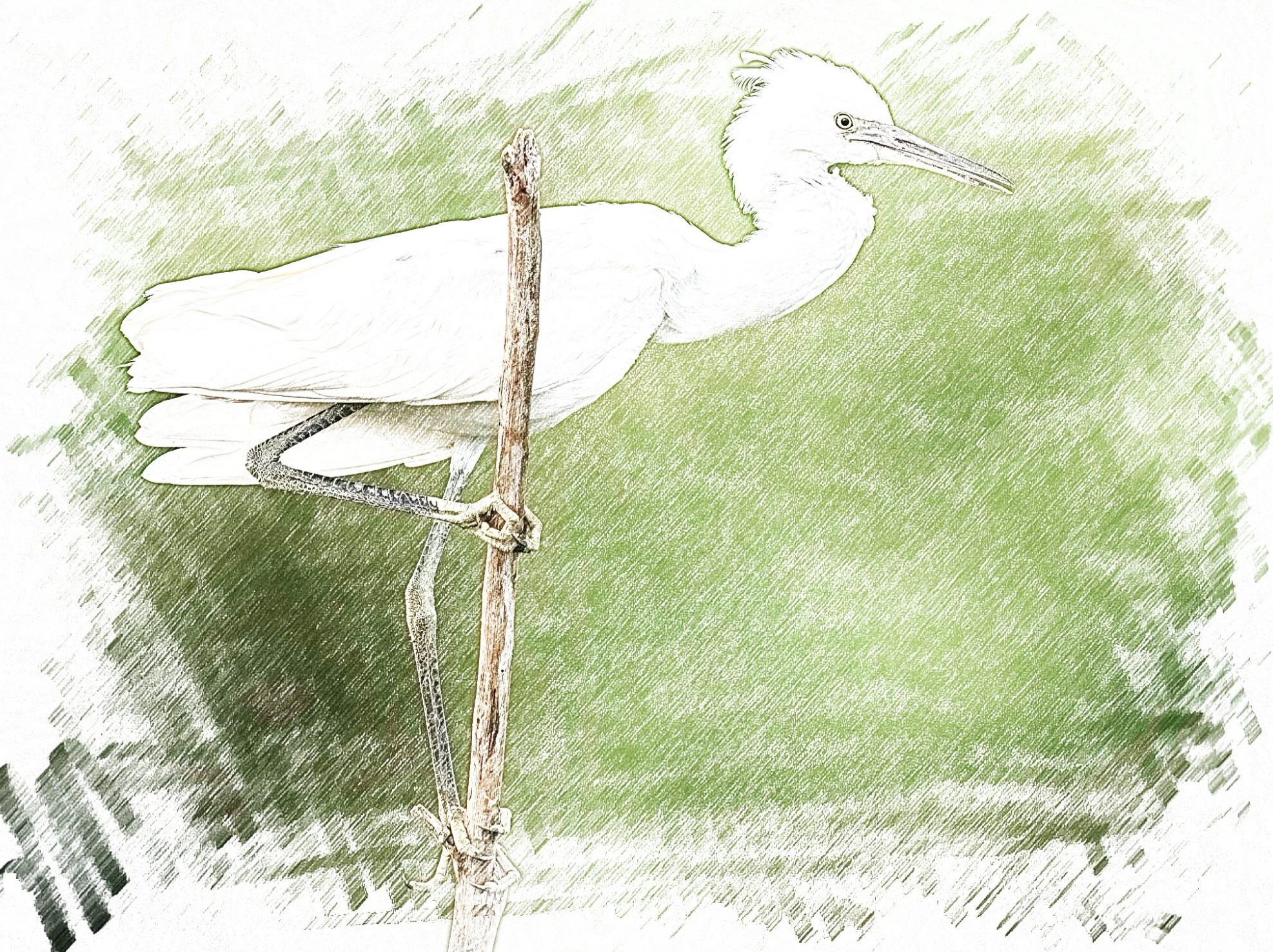

Little Egret

Egretta garzetta

Lakes & Water Bodies of Telangana & India

In 2026, the Little Egret (Egretta garzetta) remains a quintessential wildlife photography subject across Telangana’s vibrant wetland ecosystems. Often referred to locally as Chinna Tella Konga, these graceful herons provide a dynamic photography experience as they "dance" through the shallows of urban and rural lakes.

Telangana's landscape is dotted with ideal habitats, from the urban oases of Ameenpur Lake, Osman Sagar, HImayat Sagar, Kistareddypet Lake near Hyderabad to the sprawling Singur Dam, the Sri Ram Sagar Reservoir and the Dindi Reservoir. Discerning photographers often seek the "golden slippers"—the bright yellow feet—which create a sharp contrast against dark mud or blue water. It is truly an amazing experience to capture the intricate details of their breeding plumes during the peak season. Renowned for its extensive natural resources, breathtaking scenery, and rich cultural legacy Telangana is the eleventh largest state in India situated on the south-central stretch of the Indian peninsula on the high Deccan Plateau. It is the twelfth-most populated state in India with a geographical area of 112,077 km² of which 21,214 km² is forest cover. The dry deciduous forests ecoregion of the central Deccan Plateau covers much of the state, including Hyderabad. The characteristic vegetation is woodlands of Hardwickia binata and Albizia amara. Over 80% of the original forest cover has been cleared for agriculture, timber harvesting, or cattle grazing, but large blocks of forest can be found in the Nagarjuna Sagar - Srisailam Tiger Reserve and elsewhere. The more humid Eastern Highlands moist deciduous forests cover the Eastern Ghats in the eastern part of the state. The Central Deccan forests have an upper canopy at 15–25 meters, and an understory at 10–15 meters, with little undergrowth.

The dry sub-humid zone or Dichanthium-cenchrus-lasitrrus type of grasslands are prevalent here and cover almost the entirety of peninsular India except the Nilgiris. One sees thorny bushes like the Acacia catechu or Khair as it is known in Hindi, Mimosa, Zizyphus (Ber) and sometimes the fleshy Euphorbia, along with low trees of Anogeissus letifolia or Axle Wood, Soymida febrifuga - the Indian Redwood - and other deciduous species. Sehima (grass) which is more prevalent on gravel is about 27% of the cover and Dichanthium(grass) which flourishes on level soil is almost 80% of the coverage.

Telangana's extensive network of lakes, which enhance the state's scenic appeal and serve a vital role in delivering water for irrigation, home usage, and industrial reasons, is one of the state's most notable natural characteristics. Telangana has lakes due to its geography and the copious amounts of rain that fall there during the monsoons. Telangana is home to some of India's most stunning and ecologically significant water features, with over 6,000 natural and man-made lakes. Endowed with a rich natural resource base and a diverse environment, there are many lakes in the area, both natural and man-made, which are significant water supplies for industry, domestic use, and irrigation. The lakes of Telangana are a crucial component of the area's ecosystem and provide a habitat for many different plant and animal species. Many of the state's numerous lakes, which range in size and depth and provide visitors with breathtaking views and leisure activities like boating, fishing, and bird watching, are well-liked tourist destinations. Telangana's lakes visually represent the state's natural beauty and ecological diversity, from the picturesque Hussain Sagar Lake in Hyderabad to the tranquil Pakhal Lake in the Warangal district.

Sri Ram Sagar Project Environs

The Sri Ram Sagar Reservoir (SRSP), also known as the Pochampadu Project, is a critical multipurpose wetland ecosystem located on the Godavari River in the Nizamabad and Nirmal districts of Telangana. While primarily an irrigation and hydroelectric project, its vast backwaters and diverse catchment areas have evolved into a vital refuge for regional wildlife.

The reservoir and its environs support a complex mosaic of aquatic and terrestrial habitats, including deep open waters, shallow marshes, reedbeds (Phragmites and Typha), and adjacent deciduous forest patches like the Mallaram Forest. The backwaters are a major destination for migratory birds. Notable sightings include the Common Crane, which migrates from Europe to winter here, and various species of storks, ducks, and teals. Resident species such as Peacocks and various "rare birds" are frequently observed in the surrounding scrub and forest areas. The environs are home to various ungulates, including Spotted Deer/Chital, which roam the project area. The proximity to forest patches allows for a crossover of smaller mammals such as Indian Hares and Jackals.

The Godavari River system at this location supports over 26 fish species, dominated by the order Cypriniformes. Common fish include major carps and various catfish, which sustain both the local avian predators and a vibrant fishing industry. The riverbed and banks feature a diversity of aquatic macrophytes, including 30 different species of submerged, free-floating, and emergent plants (e.g., Typha angustifolia) that provide essential nesting material for birds like the Streaked Weaver.

Criticality as a Habitat

The SRSP serves as a "lifeline" for wildlife in the Deccan plateau for several reasons:

Water Security: It provides a perennial water source in a semi-arid region, crucial for both resident and migratory species during the dry summer months.

Nesting Grounds: The dense reedbeds along the shoreline are indispensable for communal nesters like the Streaked Weaver and various heron species.

Migratory Stopover: As a significant inland wetland, it serves as a critical stopover and wintering site along migratory flyways for waterbirds.

Despite its ecological importance, the reservoir faces several escalating threats:

Sedimentation: India's reservoirs, including SRSP, are losing significant storage capacity due to siltation caused by agriculture-driven soil erosion and deforestation in the upstream catchment areas. As of 2025, SRSP's actual retention capacity is significantly lower than its original 90 TMC design due to this silt build-up.

Water Quality Issues: Extensive upstream water utilization in Maharashtra has led to high alkalinity and salinity in the reservoir, which can be detrimental to sensitive aquatic life and cattle.

Structural and Safety Risks: In late 2025, dam safety warnings issued for related projects (like the Singur Dam) highlighted the broader risk of structural damage and the need for restricted storage levels, which can disrupt the stable water levels required for shore-nesting birds.

Invasive Species: The spread of exotic aquatic plants can choke native vegetation and alter the habitat structure of the marshes.

The backwaters of SRSP offer a serene, lush landscape perfect for bird photography. The most productive months for photographing these weavers are during the monsoon (June to September) when males are in their vibrant breeding plumage and actively building nests. Look for dense patches of reeds (Phragmites) and cattails (Typha) along the shoreline, which are their preferred nesting sites. They are highly social; you will often find them in large, vocal flocks.

Little Egret

The Little Egret (Egretta garzetta) is a species of small heron in the family Ardeidae. It is a small snow-white heron with a slender black beak, long black legs and, in the western race, yellowish feet ("golden slippers"). The breeding adult has 2 long wispy head plumes and a spray of white plumes ("aigrettes") on the lower back. As an aquatic bird, it feeds in shallow water and on land, consuming a variety of small creatures. It breeds colonially, often with other species of water birds, making a platform nest of sticks in a tree, bush or reed bed. It inhabits a wide variety of wetlands: lakes, rivers, marshes, estuaries—almost anywhere with small fish and occurring as singles or small loose groups; nests and roosts communally. A distinctive bird within its range comparable with the larger Great and Intermediate Egrets, the stockier Cattle Egret, and white morph reef herons. Its breeding distribution is in wetlands in warm temperate to tropical parts of Asia, Africa, Australia, and Europe. A successful colonist, its range has gradually expanded north, with stable and self-sustaining populations now present in the United Kingdom.

In warmer locations, most birds are permanent residents; northern populations, including many European birds, migrate to Africa and southern Asia to over-winter there. The birds may also wander north in late summer after the breeding season, and their tendency to disperse may have assisted in the recent expansion of the bird's range. At one time common in Western Europe, it was hunted extensively in the 19th century to provide plumes for the decoration of hats and became locally extinct in northwestern Europe and scarce in the south. Around 1950, conservation laws were introduced in southern Europe to protect the species and their numbers began to increase. By the beginning of the 21st century the bird was breeding again in France, the Netherlands, Ireland and Britain. Its range is continuing to expand westward, and the species has begun to colonise the New World; it was first seen in Barbados in 1954 and first bred there in 1994.

Physically the Little Egret is a medium-sized wader, typically measuring 55–65 cm in length. Its weight ranges from 300 to 700 grams, with most adults averaging between 350 and 550 grams. It’s wingspan is approximately 88–106 cm. It has entirely white plumage, a slender black bill, and long black legs ending in distinctive yellow feet.

Globally it is widespread across Europe, Africa, Asia, and Australia. From an Indian & Telangana context it is a widespread resident across the Indian mainland. In Telangana, it is common year-round in wetland habitats, though some local movement occurs depending on water availability.

While many taxonomists consider various forms as separate species, the primary recognized subspecies include:

Egretta garzetta garzetta (Nominate): Found in Europe, Africa, and most of Asia (including India). It is all-white with blue-grey lores that turn pink/red during courtship.

Egretta garzetta nigripes: Found in Indonesia and the Philippines. It features black feet (sometimes with yellow soles) and yellow facial skin.

Egretta garzetta immaculata: Native to Australia; it has yellow lores that turn red during breeding.

Plumage Note: Rare dark morphs (slate-grey) exist but are exceptionally uncommon in the nominate range.

Its preferred habitats are shores of lakes, rivers, canals, marshes, and flooded land. They are highly adaptable to man-made environments like rice fields and fish ponds. The diet consists primarily of small fish, but also amphibians (frogs/tadpoles), crustaceans (prawns/crabs), and insects (dragonfly larvae, beetles). They use "active" methods, often foot-stirring in the mud to flush out prey or running through shallow water with wings raised to confuse fish.

In Telangana, they are largely residents. However, northern populations (Europe/Northern Asia) are migratory, moving south to Africa or South Asia for winter. They nest colonially in "heronries," often sharing trees with Cattle Egrets and Night Herons. During breeding, they grow two long, ribbon-like nape plumes and delicate "aigrettes" on the back and breast as you can see in some of the photos here. The nest is a platform of sticks in trees or reed beds which is illustrated too in my photos and a clutch typically contains 3–5 bluish-green eggs.

Conservation Status (2026): The Little Egret has been assessed as Least Concern, although BirdLife International considers subspecies dimorpha to be part of Western Reef-Heron (Egretta gularis) (which is also evaluated as Least Concern). Globally, the population is generally stable or increasing, though local declines in Telangana can occur due to wetland degradation and pollution. In India, they are protected under Schedule-II of the Wildlife Protection Act.

Habitat Loss and Degradation: The Little Egret often breeds near human population centers. The species is tolerant of humans, except when persecuted, as evidenced by the large number of colonies (53%) that are in or close to human habitation. As in Europe, worldwide rice fields and fish farms now provide important feeding areas. In some areas, the Little Egret has grown dependent on fish ponds, and the loss of fish pond habitat in Hong Kong has caused a decline in the nesting population there (164). Preservation of fish ponds and rice fields is clearly critical.

The Little Egret is negatively impacted by contaminants from nearby agricultural and industrial operations, and attention to such pollutants might benefit egret populations. An excellent study demonstrated a strategy for conserving Little Egret in developed areas: protection of a network of colony sites from disturbance and ground predators, identification of feeding areas, active management of identified feeding habitat to retain critical characteristics, and establishment of new colony sites in appropriate feeding habitat currently lacking nesting habitat.

The Little Egret, known locally in Hindi as karchiya bagula, is a common sight in Indian wetlands, often symbolizing grace and purity. While not as prominent as the sacred white swan or peacock in major epics, it holds a place in cultural folklore as a symbol of good fortune and, in some traditions, is considered a protected, inedible bird.

Cultural and Symbolic Significance

A Symbol of Purity: Similar to other white birds in Indian tradition, the little egret is often associated with elegance and purity.

A Sign of Good Luck: It is frequently viewed as an omen of prosperity and good fortune in various regional folklore.

Dietary Restrictions: According to some interpretations of the Dharmashastra, the egret is listed among birds that should not be consumed, reflecting its place in religious or traditional, cultural, and dietary codes.

Commonality: Known for gathering in large colonies on trees, often mistaken for "fruiting" trees due to their white plumage, they are deeply integrated into the landscape of the Indian countryside.

In Ecological Context

Role in Agriculture: Often seen in paddy fields, they are respected by farmers, as they thrive on insects and grubs stirred up by agricultural activity.

Field Identification Tips

Look for "Golden Slippers": The bright yellow feet are the most reliable field mark for distinguishing them from other white egrets.

Bill Shape: Check for a very slender, straight black bill (Great Egrets have yellow bills; Intermediate Egrets have shorter, thicker bills).

Size: Noticeably smaller and slimmer than the Great Egret.

Flight Style: Flies with its neck retracted in an 'S' shape and feet extending well beyond the tail.

‡‡‡‡‡

Related Posts